Carl’s hopes for a music career and playing his violin were altered June 23, 1998, when his Camry was struck by a delivery truck early one morning as he delivered newspapers–his summer job between semesters at Hillsdale College.

He describes his recovery.

“Broken bones?” I asked.

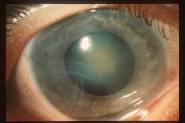

“Many, many, many. If you want me to go from top to bottom,” he pointed to his head: “Traumatic brain injury. My skull was never fractured, so that was a mercy of God right there. What they said, the right side of my brain twisted on the stem and rubbed up against the right side of my skull. That is what put me in a coma. Major gash on the left side of my skull. The scalp was open, so I had stitches there. Going down, my left collar bone was broken.”

“Many, many, many. If you want me to go from top to bottom,” he pointed to his head: “Traumatic brain injury. My skull was never fractured, so that was a mercy of God right there. What they said, the right side of my brain twisted on the stem and rubbed up against the right side of my skull. That is what put me in a coma. Major gash on the left side of my skull. The scalp was open, so I had stitches there. Going down, my left collar bone was broken.”

I couldn’t resist, “You had your seat belt on, right?” Hey, I’m a mom.

“That’s what saved my life. I wore my seat belt and the air bag deployed. Both my arms and both my legs were fine, but everything else in my torso was messed up, except for my back. All my ribs were broken, resulting in both lungs being punctured. My pelvis, that’s the big bone, got broken in five places. While I was in a coma, they weren’t able to move my legs until my pelvis healed. Calcium deposits started forming under my kneecaps, completely shifting my kneecaps out of their normal spot. When I emerged from the coma, I didn’t have knees. I had lumps and wasn’t able to walk.”

After more than five months of rehab, Carl was able to go home.

“I came home the day before Thanksgiving. I was so thankful to God that I was alive, so thankful to be coming home, though my emotions were a little dampened. I just didn’t seem…my emotions were pretty numbed.

“I did start trying to play the violin. I wanted to play for carol sing, like I had done in the past. I tried. I really did. It was frustrating. My left hand doesn’t work. I did play, but I wasn’t at the level I wanted.”

Carl put his violin down after that.

“It’s neurological damage. Something is messed up between my brain and my hand.”

“It’s neurological damage. Something is messed up between my brain and my hand.”

“What do you think about that,” I asked.

“All right, God. What do you want me to do now?”

He had wanted to be a music teacher.

“And, now I can’t do anything musical, really. I think God was saying, ‘Trust Me, I will lead you.’ It ended up being an experience, gradually learning to trust God. There is still hope that I could play the violin, That has never left.”

Carl took community college classes that fall, then returned to Hillsdale. “I was thrilled to be back, but things weren’t as I remembered.

I wasn’t quite so…I’m a lot sadder, more sedate than I was used to being.”

He struggled to explain the (neurological) loss of emotion. He did graduate from Hillsdale, a degree in music pedagogy.”

“Music pedagogy was kind of a major they made for me. I have head knowledge, but I can’t do the physical expression.”

Our lunch at Appleby’s had had several distractions. Just then Carl saw a young woman he knew. They bantered about winter break and school being superior to employment.

“Reality,” I said.

“Reality sucks,” he responded.

“Stay in school as long as you can.”

He was sheepish, realizing this was a more candid, present, than the narrative we had been focusing on.

By 2004 Carl was weighing his options.

“Is music still a hope?” I asked.

“A very distant hope,” he said. “If I were able to play again, I think I would get back the emotion.”

“The music itself could bring it back?”

“I think so.”

He’s currently (2005) studying counseling at a seminary in St. Louis.

“What’s happening inside Carl,” I asked.

“I’m really not sure. To a certain extent, I feel a little loss of direction.”

“Do you see purpose in all of this?”

“I know there is. I don’t know. I know there is one. I’ve never had a normal life, even pre-DAO (Divinely Appointed Occurrence). That’s what I call my wreck. God does not cause sin, but he has a purpose through it, and that is a mystery which, this side of heaven, we will never be able to fathom.”

“Are you OK with that?”

“I am more than OK with that.” He paused.

“I should be honest. There are other things that come into play.” He described social struggles.

“I should be honest. There are other things that come into play.” He described social struggles.

He’s 25. It’s a difficult young adulthood.

“What you want back is your passion for life?”

“Yes.” “I think we’re still talking about perfect pitch,” I said.

“Emotional perfect pitch., knowing what you’re missing. It hurts.”

He reflected. I had hit a chord. His friends were IM-ing him again.

“Do you mind if I check my phone?” he asked.